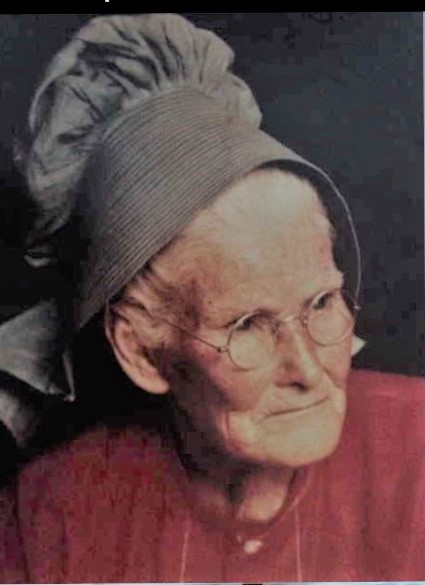

My Quest for Native American Ancestry Began with a Photograph

My quest to learn more about my ancestors began with a photograph of my great-grandmother that appeared in a newspaper sometime in the late 1940s. The image was captioned simply: “Lady in a Sun Bonnet.”

The accompanying article read:

“The pioneer Kentucky mountain families of the Cornetts and Isons gathered recently for a reunion along Leatherwood Creek in Perry County. One of the most striking persons present was Mrs. Polly Ann Cornett. Her snow-white hair was accentuated by a bright red waist. Her love for red, she explained, was inherited from Indian ancestry. Her paternal grandfather was Indian. She recalled that her brother always wore a red necktie. Her brother is Hiram Brock, a state senator and political leader in Eastern Kentucky for many years.”

Indian ancestry?

This was the first I had ever heard of it.

So I asked my dad.

“Oh yeah,” he said casually. “We have some Indian blood in the family.”

That was pretty much the extent of what anyone seemed to know.

At the time, all I really understood about my family tree was that my dad was born and raised in Eastern Kentucky—Harlan County—and my mom was born in Oklahoma. I had red hair, blue eyes, freckles, and very fair skin. My mom had blondish hair, blue eyes, and fair skin. My dad had black hair, blue eyes, and tanned easily.

Long before DNA testing was a thing, I began researching my dad’s side of the family the old-fashioned way. I eventually traced his lineage back to a Cherokee chief named Chief Red Bird, who would be my fifth great-grandfather. But the Native blood went back even further than that.

In the early frontier days, it was not uncommon for settlers—often mountain men—to take Native wives. Over generations, that bloodline eventually culminated with Red Bird. From there, as families moved out of the Kentucky hollers and intermarried, the ancestry became increasingly European.

Years later, when online DNA testing became readily available, I had my dad—at 99 years old—spit into a 23andMe tube. The results showed 2% Indigenous ancestry. Through additional research, I also found Shoshone ancestry in the mix.

I solved one family mystery but learned about another tribe where my DNA is the strongest.

The Celts

The Celts, much like Native Americans, were peoples who were tribal in structure—bound by clans, kinship, land, and oral history. Peoples whose spiritual traditions were ancient, whose ceremonies and beliefs stretched back thousands of years bound by nature.

The Erasure

Long before the colonization of the Americas, England had already honed its appetite for conversion at home. Celtic peoples in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales were targeted not just for their land, but for their beliefs. Conversion was framed as salvation, but it functioned as control. Oral traditions were discouraged or destroyed, sacred sites were repurposed, clan systems were dismantled, and spiritual practices were labeled pagan, savage, or uncivilized—language later reused almost verbatim in the New World. Celtic children were taught that their native tongues were backward or shameful, a strategy later replicated almost exactly in Native American boarding schools. When a language is erased, so too are the stories, ceremonies, and meanings that cannot be translated.

Much of the Celtic tribal belief system was lost—not because it was primitive or weak, but because it was deliberately dismantled through conquest, forced conversion, and the erasure of oral tradition. What remains are fragments: folklore, language, seasonal customs, and a lingering sense of belonging to land and kin—echoes of what once was whole.

Christianity was the primary tool used to justify cultural erasure, but the driving force was political control. Conversion wasn’t only about faith; it was about obedience. Indigenous belief systems—Celtic and Native alike—were deeply tied to land, kinship, and autonomy. By replacing those systems with Christianity, empires weakened tribal authority, disrupted oral traditions, and made people easier to govern. The church and the state worked hand in hand: religion supplied the moral justification, while empire reaped the land, labor, and loyalty.

Native peoples of the Americas, despite immense pressure and violence, managed to preserve far more of their living traditions – albeit through oppression and loss. And perhaps that is why the interconnection still feels present—one culture holding what another was forced to forget.

This pattern of cultural erasure extended beyond Native peoples. Those forcibly brought to the Americas were also stripped of language, tradition, and identity, their histories intentionally fractured as a means of control.

I guess what I learned is that I come from strong tribal roots, abroad and here in the Americas – both part of the European cultural erasure.

It all began with a single photograph that asked a question with even more to the answer than I had imagined.

You must be logged in to post a comment.