Me on Frog Lake Overlook.

When the Mountain Says No: A Memory of Frog Lake

I still remember the first time I hiked toward Frog Lake Overlook in the Sierra of Northern California.

It was summer. Blue sky. Warm sun. Wildflowers scattered along the trail like confetti. And even then — even in perfect weather — it wasn’t easy. The trail climbed steadily, the air thinned, and the slopes around us felt big and exposed. It was hot, and I got overheated. At one point I honestly didn’t think I’d make it to the top, but I pushed forward.

I stopped more than once, hands on my hips, catching my breath and looking up at those towering ridgelines, thinking: This place is beautiful… but it’s serious. No joke.

In winter, that same beauty becomes something entirely different. Those open slopes fill with deep snow. Terrain that feels challenging in July turns avalanche-prone and unforgiving. It’s why the area is beloved by experienced backcountry skiers — and why it demands careful judgment every single time.

This week, that place took nine lives.

And I can’t stop thinking about how easily excitement, planning, and commitment can blur the most important decision we ever make outdoors: whether to go at all.

My husband was a private pilot for many years, and aviation teaches this lesson brutally and early. There’s a phrase pilots use: “get-there-itis.”

You plan the trip. Check the weather — all good. Drive to the airport. Then conditions change. You see holes in the clouds and start wondering: Can I get above this? Will it clear… or close in?

We’ve waited it out. We’ve diverted. We’ve cancelled entirely and driven home.

Because experienced pilots know something simple and hard:

The safest flight is the one you don’t take.

“Get-there-itis” kills pilots every year.

And sometimes, it shows up in the mountains too.

Forecasts had warned that the Sierra was about to be hammered with massive snowfall — feet upon feet in a very short time. Anyone familiar with the range knows what that means: unstable snowpack, hidden weak layers, and avalanche danger that escalates fast.

The Frog Lake huts are booked far in advance are NOT cheap and often more than a year out, with strict cancellation policies. That kind of reservation can quietly add pressure. After waiting that long, it’s human to feel like you have to go.

But mountains don’t honor reservations.

My perspective, from someone familiar with the area:

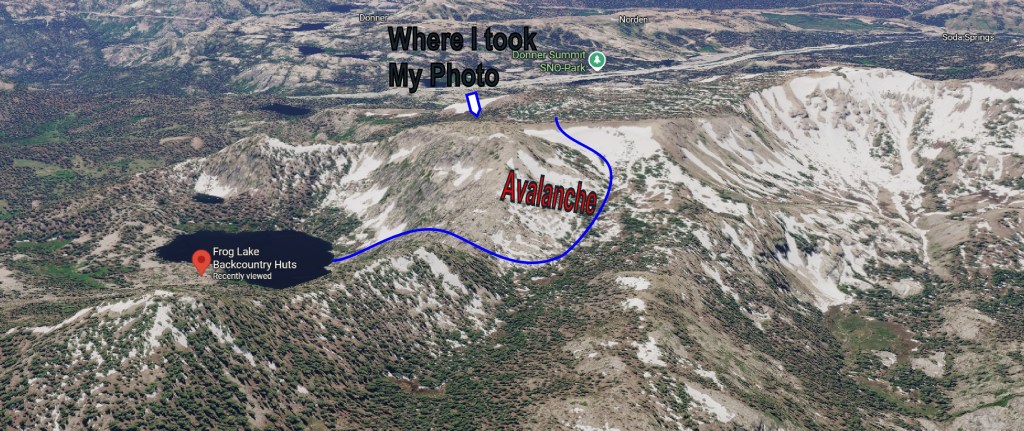

There are three routes out from the huts according to the Land Trust Website. Two of them cross the steep, avalanche-prone saddle, leading toward parking areas near I-80 and the Castle Peak trailhead — less than half a mile apart. Another option heads east along the flatter service road and heads east towards the Truckee area. Or, another option not mentioned by the Trust, is to cut over towards Summit Lake. With some backcountry navigation, that route can also be used to loop back toward the trailhead. In fact, another party reportedly used that approach to avoid the avalanche-prone saddle.

The huts themselves are modern, heated, and staffed with a full-time caretaker. Staying put could potentially have allowed rescuers to reach the group more safely once conditions improved. Skiing out over that saddle — especially during or just after a major storm — would be extremely dangerous. Also, the storm was raging and they were at risk of dying from exposure!

Of course, that’s easy for me to say from the comfort of home. I’m a backcountry hiker, not a backcountry skier. But I’ve done enough snowshoeing in that area to know how serious those winter conditions can be.

The Routes Suggested by the Tahoe Land Trust

What we do know is what followed.

Search-and-rescue crews had to enter whiteout conditions and severe avalanche danger to reach the survivors. For hours, rescuers put their own lives on the line in terrain that was actively unstable. That’s what these teams do — but every risky decision in the backcountry ripples outward, placing others in harm’s way too.

This isn’t about pointing fingers. It’s about recognizing something deeply human.

We all feel the pull to keep going.

To finish what we started.

To not waste the opportunity.

But experience — real experience — teaches a quieter truth:

Turning back isn’t failure.

Waiting isn’t weakness.

Cancelling isn’t defeat.

Sometimes it’s:

The decision to stay in the hut and wait it out.

The willingness to cancel the trip altogether.

I think back to the summers of hiking to Frog Lake — the sunlight, the wildflowers, the sheer effort it took even in calm conditions — and this week’s loss feels even heavier.

Nine families are now living with the reality that the mountain will always be there…

…but their loved ones aren’t.

If there’s anything this tragedy leaves us with, it’s this:

The wilderness rewards skill and preparation.

But it demands humility.

And sometimes the most experienced thing we can do

is listen when the mountain says no.

—